|

Category

|

Uzbek cuisine

The seasons, specifically winter and summer, greatly influence the composition of the basic menu. In the summer, fruits, vegetables, and nuts are ubiquitous. Fruits grow in abundance in Uzbekistan - grapes, melons, apricots, pears, apples, cherries, pomegranates, lemons, figs, dates. Vegetables are no less plentiful, including some lesser known species such as green radishes, yellow carrots, dozen of pumpkin and squash varieties, in addition to the usual eggplants, peppers, turnips, cucumbers and luscious tomatoes.

In general, mutton is the preferred source of protein in the Uzbek diet. Fatty-failed sheep are prized not only for their meat and fat as a source of cooking oil, but for their wool as well. Beef and horsemeat are also consumed in substantial quantities. Camel and goat meat are less common. The wide array of breads, leavened and unleavened, is a staple for the majority of the population. Flat bread, or nan, is usually baked in tandoor ovens, and served with tea, not to mention at every meal. Some varieties are prepared with onions or meat in the dough, others topped with sesame seeds or kalonji.

Palov, the Uzbek version of "pilaff", is the flagship of their cookery. It consists mainly of fried and boiled meat, onions, carrots and rice; with raisins, barberries, chickpeas, or fruit added for variation. Uzbek men pride themselves on their ability to prepare the most unique and sumptuous palov. The oshpaz, or master chief, often cooks palov over an open flame, sometimes serving up to 1000 people from a single cauldron on holidays or occasions such as weddings. It certainly takes years of practice with no room for failure to prepare a dish, at times, containing up to 100 kilograms of rice.

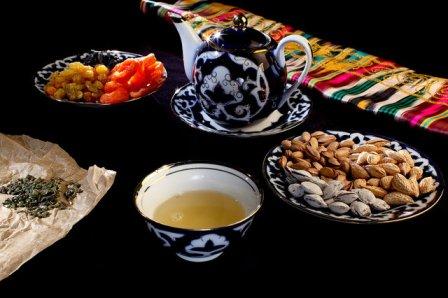

Tea is revered in the finest oriental traditions. It is offered first to any guest and there exists a whole subset of mores surrounding the preparation, offering and consuming of tea. Green tea is the drink of hospitality and predominant. Black tea is preferred in Tashkent, though both teas are seldom taken with milk or sugar. An entire portion of their cuisine is dedicated solely to tea drinking. Some of these include samsa, nan (bread), halva, and various fried foods. The "choyhona" (teahouse) is a cornerstone of traditional Uzbek society. Always shaded, preferably situated near a cool stream, the choyhona is gathering place for social interaction and fraternity. Robed Uzbek men congregate around low tables centered on beds adorned with ancient carpets, enjoying delicious palov, kebab and endless cups of green tea. In preparing the article draws Site http://www.uzbekcuisine.com/ |

One particularly distinctive and well-developed aspect of Uzbek culture is their cuisine. Unlike their nomadic neighbors, the Uzbeks have had a settled civilization for centuries. Between the deserts and mountains, in the oasis and fertile valleys, they cultivated grain and domesticated livestock. The resulting abundance of produce allowed them to express their strong tradition of hospitality, which in turn enriched their cuisine.

One particularly distinctive and well-developed aspect of Uzbek culture is their cuisine. Unlike their nomadic neighbors, the Uzbeks have had a settled civilization for centuries. Between the deserts and mountains, in the oasis and fertile valleys, they cultivated grain and domesticated livestock. The resulting abundance of produce allowed them to express their strong tradition of hospitality, which in turn enriched their cuisine. The winter diet traditionally consists of dried fruits and vegetables and preserves. Hearty noodle or pasta-type dishes are also common chilly-weather fare.

The winter diet traditionally consists of dried fruits and vegetables and preserves. Hearty noodle or pasta-type dishes are also common chilly-weather fare. Central Asia has a reputation for the richness and delicacy of their fermented dairy products. The most predominant - katyk, or yoghurt made from sour milk, and suzma, strained clotted milk simmilar to cottage cheese, are eaten plain. In salads, or added to soups and main products, resulting in a unique and delicious flavor.

Central Asia has a reputation for the richness and delicacy of their fermented dairy products. The most predominant - katyk, or yoghurt made from sour milk, and suzma, strained clotted milk simmilar to cottage cheese, are eaten plain. In salads, or added to soups and main products, resulting in a unique and delicious flavor. Uzbek dishes are not notably hot and fiery, though certainly flavorful. Some of their principle spices are

Uzbek dishes are not notably hot and fiery, though certainly flavorful. Some of their principle spices are