|

Category

|

The History of Uzbekistan

During the Neolith (6000-4000 BC) three extensive archaeological cultures developed in Central Asia: Jeitun, Gissar and Keltiminar. Settled crop growing cultures progressed during the Neolithic (circa 4000 BC) and especially Bronze Age (3000-2000 BC), when bronze tools and weapons came into use. In the second half of the 2nd millennium BC the first city-states appeared in the most advanced regions in Central Asia. Their structure resembled that of ancient Egyptian city-states which included a large settlement (administrative centre) surrounded by oases and several smaller settlements situated along a canal or river.

In 539 BC (or 529 BC, according to other sources) Central Asia came under the control of the Achaemenid king Cyrus of Persia. The king himself was killed in a battle with the Sakas under Queen Tomiris. During the next two centuries the southern part of Central Asia was annexed by the Persian Empire and divided into satrapies which paid tribute in silver to the kings. Three of the satrapies – Bactria, Sogd and Khoresm – lied within the territory of present-day Uzbekistan.

After the death of Alexander and subsequent turmoil, in 306 BC the southern portion of Central Asia became part of the Seleucid Empire. Later, in the mid-3rd century BC, the rebellious Bactrian satrap Diodotus established an independent kingdom which became known as Greco-Bactria. In the second half of the 2nd century BC, Greco-Bactria fell to the invading Sakas and Sarmatians, and then was overrun by the Yue-chi (Kushans) who were driven into the region by the Huns. Eventually, a loose confederation of virtually independent petty states was established in the area. A like state, Kangyui, emerged in the 2nd century BC in Transoxiana which, according to Chinese sources, consisted of five domains, each coining its own money. Later in the 2nd century BC Han China familiarised itself with "the Western Land" (i.e. Central Asia), and the Great Silk Road emerged as the first major transcontinental route connecting the West and the East.

The 3rd and 4th centuries AD saw the fall of the great Parthian and Kushan empires, the rise of a host of petty kingdoms in Central Asia, intrusions by nomadic tribes, the destruction of the ancient social formation, and a decline in economy, arts and culture.

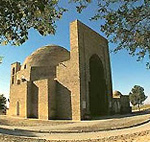

In the 7th-8th centuries Transoxiana was divided into a number of ethnically non-uniform city-states; the most prominent of them were Gurganj (present-day Kunya-Urgench), Bukhara, Samarkand, Chaganian (near present-day Denau) and Chach. Religious beliefs were as diverse. Zoroastrianism dominated the region; Manichaeism and Christianity also spread widely, and Buddhism was practiced in the south. In the mid-7th century Arabs came to play an increasingly important role in Central Asian politics. They captured Merv in 651 (near present-day Bairam-Ali, Turkmenistan) and made it a stronghold from which to raid Transoxiana. Since then, this land was known as Maverannahr (Arabic for "that which is across the river"). Military expeditions by the Arabs, especially under Kuteiba ibn Muslim in 704-712, resulted in all of Transoxiana becoming part of the Abbasid caliphate. The conquerors brought Islam to the region, and in the 9th century it became the state religion for the peoples of Central Asia.

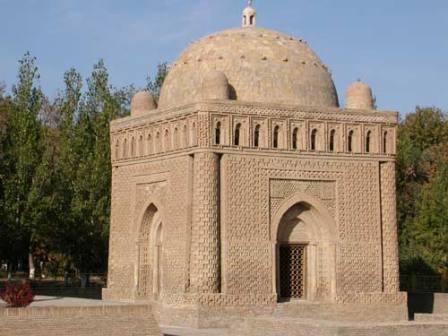

The beginning of this process can be attributed to the period of the Barmakids, whose ancestors were Buddhist high priests from Balkh. In the early 9th century the northeast provinces of the caliphate were united under the Takhirid dynasty (821-874) founded by Takhir ibn Hussein. In 821 he was made the governor of Khorasan, which at that time covered nearly all the northeast domains of the caliphate, including Maverannahr with Bukhara, Samarkand and Chach. Takhir ruled the area as an independent monarch and coined his own money. Eventually, in 822, he ordered not to mention caliph Mamun in “khutba” (Friday prayer), which indicated gaining full independence according to Muslim traditions. The peak of the Takhirid’s power occurred under Abu-al Abbas Abdallakh ibn Takhir (830-844), who consolidated his domain as a true sovereignty. He strengthened the political and administrative power and enforced radical reforms in agriculture, water supply, crafts, mining, taxation and monetary system. The Takhirid period was also the time of the final victory of Islam in Maverannahr. The Takhirid rulers were succeeded in Maverannahr by the Samanids.

The 11th-13th century. The last Samanid ruler, Abu Ibrahim Ismail the Muntasir (Arabic for "victorious"), was killed in 1005, and his state was divided between two khanates under the Turkic dynasties of the Karakhanids and Gaznevids. The Karakhanid khanate was founded in the 10th century by Satuk, a Turkic convert. His son Musa made Islam the state religion in 960.

The latter dynasty was founded by Sebuk, a former priest, and attained its peak of power under sultan Mahmud (998-1030). Mahmud’s state, with capital at Gazna, included vast territories from the Caspian Sea to North India and part of present-day Uzbekistan. After Mahmud’s death his possessions gradually shrank, with Khorasan and Maverannahr coming under the control of the Seljukids and Karakhanids. In the 1240s khan Ibrahim the Tamgach put an end to dependence on the eastern Karakhanid khanate and established an independent state in Maverannahr, making Samarkand his capital. During his reign the territory of his khanate was extended to include all of Maverannahr, Chach, Ilak and Fergana. The Karakhanids’ state consisted of a number of dependencies whose rulers were essentially independent monarchs and even coined their own money; this was the principal weakness of the dynasty. The khanate was exposed to permanent pressure from external foes, the Seljukids and later, in the 12th century, the Kara-Kitai. The Seljukids built a vast empire which extended from Byzantium in the west to Tokharistan in the east, and flourished under Ali-Arslan (1063-1078) and Malik- Shah (1078-1093). Its capital was at Merv. In the late 1330s a new formidable power, Kara-Kitai, emerged on the eastern border of the khanate; by this name Muslim writers meant a nomadic Manchu people originating from the Tarim basin (East Turkistan). In 1141 the Kara-Kitai destroyed the allied armies of the Seljukids and Karakhanids in a battle in the Katvan steppe. The population of Maverannahr was imposed a heavy tribute – a dinar from each household – to be delivered to the military capital of the Kara-Kitai at Balasagun. However, the Karakhanids retained administrative control of the state, although it shrank in size dramatically. In Bukhara, the power was usurped by the “sadrs” (Arabic for "column"), a religious dynasty who claimed descent from caliph Omar. Later in the 12th century the Karluks, traditional enemies of the Karakhanids, began to settle in Maverannahr. At the same time the southern part of Uzbekistan was invaded by the Gurids, an Afghan dynasty from the mountainous region of Gur. The Karakhanid state was no longer a whole: in Samarkand, Chach, Fergana, Chaganian and Termez the descendants of the Karakhanids established their own royal houses.

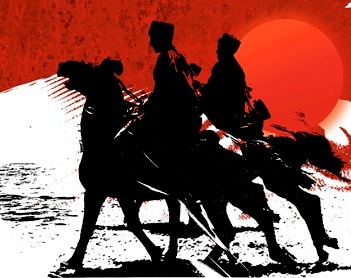

The 13th-15th centuries. The rule of Khoresm shahs came to an end in 1220, when Mongol armies under Genghis Khan swept through the country. Genghis Khan’s invasion of Uzbekistan began in early 1220. The Mongols sacked Bukhara in February, Samarkand in March and Termez in autumn; Gurganj fell in April next year. All these cities were razed by the invaders, and some of them, including Samarkand and Termez, were later rebuilt in new locations. After the death of Genghis Khan in 1227 his vast empire split into several parts governed by his sons and grandsons. The northwest part of Uzbekistan joined the Golden Horde, possession of Genghis Khan’s firstborn Juchi, and the remaining part of the country passed to his brother Jagatai (1227-1241). Khan Kepek (1318-1326), a Jagataid, moved his capital to Maverannehr. He built a palace near Nesef (Karshi in Mongol), which became the core of a large new city of Karshi (administrative centre of the present-day Kashkadarya viloyat). During the reign of Tarmashirin (1326-1334) who was converted to Islam, friction developed between two fractions of Mongol nobles; one of them advocated adopting Islam and settled lifestyles, and the other strongly adhered to nomadic traditions and pagan beliefs. This strife culminated in the country’s division into Maverannahr proper and Mogulistan (the area of present-day Jetysuu, East Kazakhstan-North Kyrgyzstan). As a result of collisions between the two movements and feudal faction, in the late 1350s Jagatai’s domain dissipated into more than a dozen petty states. In the mid-14th century Amir Temur, founder of one of the greatest empires in the East, first rose to prominence in Maverannahr. He was born in 1336 in Kesh, which later was renamed Shakhrisyabz.  In April 1370 a kurultai (congress) in Balkh elected Amir Temur the supreme ruler of Maverannahr. However, Amir Temur declined the title of khan on account of not being a Genghisid, taking instead the somewhat inferior title of emir. He enthroned a nominal khan, Suyurgatmysh (1370-1388), and later his son Sultan Mahmud (1388-1402), as dummy rulers. In 1380 Amir Temur finally settled internal faction and led military expeditions to Jetysuu, Khoresm and the Syrdarya valley, with the ultimate goal of consolidating the former Jagataid possessions into a new state with capital at Samarkand.

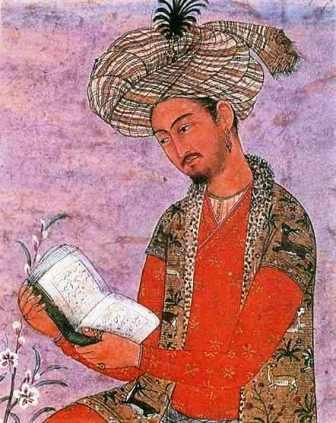

Extending his control over Bukhara and Samarkand by the early 16th century, Shaibani captured Khoresm in 1505 and Gerat in 1507; thus he put an end to the reign of the Timurids in the region. The only ruler who put up able resistance to the invaders was Babur, descendant of Amir Temur in the fifth generation. However, after his defeat in 1512 Babur retreated to Hisar, and from there made a number of raids to Kabulistan and India. Finally, in 1525, he began a decisive campaign in India which resulted in the creation of the Mughal Empire. After the collapse of the Timurid empire all of Maverannahr was divided between kindred Uzbek dynasties. Its major portion was included in a state consolidated by khan Shaibani, which flourished under khan Ubaidulla (1534-1540) and especially under Abdulla II (1583-1598). The death of Abdulla occasioned violent internal strife for power, which led to the rise of the Janid rulers (named after Jani Muhammad, founder of the dynasty). Khoresm, the lower Syrdarya valley and parts of modern Turkmenistan were controlled by another kindred dynasty founded by sultan Ilbars in 1511. When Khiva was made the capital of this domain in 1596, the state itself became known as the khanate of Khiva. In the end of the 17th century – beginning of the 18th century the region suffered a severe economic and political crisis, aggravated by continuous raids by the nomadic Kalmyks, and especially by the 1740 Persian invasion by shah Nadir. The frequently shifting khans became essentially nominal rulers backed by the leaders of various Uzbek tribes. In the mid-18th century isolationist trends in the region promoted the formation of new states.

In the beginning of the 18th century Fergana became a separate domain under Shahrukh-biy from the Uzbek tribe of Mings. One of the later rulers of this state, Alambek, assumed the title of khan in 1805, and the state became known as the khanate of Kokand (after its capital). From 1808 the khanate included Fergana, Tashkent and an area lying along the Syrdarya. In 1864 Russian troops captured Tashkent and then Fergana, and the khanate of Kokand was annexed by the Russian empire.

In the second half of the 19th century all of Uzbekistan was divided between the khanates of Kokand and Khiva and the emirate of Bukhara. Following an offensive by the Russians in the 1860s the khanate of Kokand was dissolved and designated the Turkistan Province under a Russian governor-general, and Bukhara and Khiva received the status of protectorate, becoming vassal states with a curtailed territory. The Russian colonisation had multiple implications for the peoples of Central Asia, both positive and negative. On the one hand, Tsarist Russia assisted modernisation of industrial and agricultural production in its new provinces, and promoted modern economic relations, urban development and familiarisation with the achievements of European culture. But on the whole this beneficial influence could not make up for disastrous changes to native civilisation and lifestyles.

Cotton production was of strategic importance to the empire, and the colonial administration made every effort to promote this crop. As a result, from 1889 to 1911 cotton sown areas in Turkistan increased by seven times. Turkistan played a major role in releasing Russia from dependence on cotton import, and by 1915 the proportion of Uzbek cotton on the Russian market was boosted to almost 70%. In parallel with that, areas under cereals and fodder crops shrank dramatically, resulting in the dangerously high food dependence of the region. The local industrial structure was dominated by facilities for pre-transport treatment of cotton wool. Whereas in 1873 there was a single cotton plant, in 1916 there were 350 such enterprises. At the same time production of coal, oil, ozokerite and non-ferrous metals began to develop in the area. Colonial goals totally determined the initiatives to build railways, which were laid with a view to strengthening defence, continuing territorial expansion and deploying troops in revolting areas. The migration policy pursued by the government was an important political and economic tool to expand Russian presence in the area and build a reliable social structure to support the Tsarist regime. The majority of newcomers to the region were peasants from Russian countryside. The Tsarist administration of Turkistan paid close attention to fundamental reform of local education system. Russian-Uzbek schools were opened in large numbers to provide educated local workforce. There also existed the so-called "new methodology schools" founded by the Jadids in the beginning of the 20th century, which combined the achievements of eastern and European teaching and offered both religious and secular training. The Uzbek culture continued to develop despite suppression by the Tsarist regime. This period witnessed the flourishing of such talents as Mukimi, Zavki, Furkat, Behbudi, Hodja Muin, and other writers. Traditional Uzbek and classical music, crafts and applied art also progressed. The spiritual life in Central Asia was enriched with the introduction of previously unknown cultural phenomena such as public libraries, museums, newspapers, telegraph, photography, cinema, printing, etc., and the beginning of professional Uzbek theatre and circus. Important advances were made in local science. A number of prominent Russian scientists worked in Turkistan, among them V.V.Bartold, V.L.Vyatkin, I.M.Mushketov, V.A.Obruchev, V.F.Oshanin, P.P.Semenov-Tyanshansky, A.P.Fedchenko, and others. However, the methods and forms of colonial rule and the policy of imperial unification caused increasing popular discontent. It broke out in mass disturbances and revolts – the 1875 uprising led by Dervish-khan in Andijan and Margilan, the 1892 "Choleraic Revolt" in Tashkent, the 1898 uprising of Dukchi-ishan in the Fergana valley, and the most violent insurrection in 1916, which was provoked by the tsar’s decree on forced recruiting of Uzbeks for rear service on the fronts of World War I. A new epoch in Uzbek history began after the February Revolution in Russia, which triggered rapid politicisation of Turkistan society. The National Democrats consolidated around Shuroi Islamiya, a strong party created in March 1917 by the leaders of the Jadid movement – Ubaidulla Assadullakhojayev, Munavvar Kori, Makhmudhoja Behbudi and Tashpulatbek Norbutabekov. They also assisted the rise of other political associations. The position of native population was voiced at the 1st All-Turkistan Muslims’ Congress (April 1917). The delegates recognised the Provisional Government and unanimously voted for the establishment of a federal democratic republic in Russia, with self-government for all the dependencies including Turkistan.

As before, in no way did the delegates advocate separation from Russia. The government of Turkiston Mukhtoriyati which was elected at the Congress included both Uzbek leaders and representatives of European ethnic groups. However, this movement was not in line with the Bolshevik policies, and in February 1918 Turkiston Mukhtoriyati was attacked and crushed. The following years were marked by the mass anti-Soviet basmachi (guerrilla) war. In the Fergana valley alone, about 500,000 men died fighting Soviet armies in 1918-1924. In 1920 the Soviets overthrew the khans in Bukhara and Khiva, and these two states became Peoples’ Soviet Republics under the control of Soviet Russia. The formation of the USSR in December 1922 was accompanied by unification of the socialist state system. As a result of ethnic demarcation in Central Asia, five new republics were created in 1924, including the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic. Contrary to all the propaganda on the voluntary choice made by the Uzbek people, the nation never received sovereign rights and in fact was forced into the humble position of another Soviet dependency. The Soviet era was characterised by both positive and negative developments in Uzbek economy and society. The ill-designed Soviet reform policy led to a disastrous campaign for forced collectivisation, which was meant to crown the 1917 plan to nationalise industry and agriculture totally. During the campaign over 60,000 Uzbek peasants were subjected to repressions. Collectivisation decimated the rural economy; production of livestock, cereals and other items countrywide dropped so drastically that famine struck several vast areas, including Uzbekistan. Agriculture gradually revived over the next decades, when the input supply and technical capacity of government-run farms were strengthened. Nevertheless, the kolkhoz (collective farm) system of land use and command management remained insuperable impediments to better performance.

The Soviet impact on cultural life in Uzbekistan was ambiguous. The major achievements of the Soviet period included raising the educational level of the population, creating an extensive network of colleges and universities, and making impressive advances in science, the arts and literature. But this overall progress was darkened by political purges by the totalitarian regime, which took a heavy toll on the intellectual potential of Uzbek society.

Political persecution of educated people and clergy in Uzbekistan continued into the 1940-1950s. On the whole, from 1937 to 1953 nearly 100,000 people were victimised for political reasons, and 13,000 of them were shot. In the mid-1950s the new leadership of the Soviet Union publicly condemned the mass repressions and rehabilitated many innocent victims. However, these moves were not followed up with systematic changes to the regime. In the final decades of Soviet rule important achievements in certain fields were counterbalanced by an overall tendency towards stagnation in social development and the economy. Thus, the rise of agricultural production and government measures to take full advantage of Soviet technological breakthroughs resulted in better income levels and living conditions for the population in Uzbekistan as compared with the pre-Soviet past. However, at the beginning of the 1980s the pace of economic development throughout the USSR dropped to a level which indicated the final crisis of the socialist economic system. Uzbekistan’s specialisation as a raw materials supplier became absolute in the 1960-1980s. The treatment of Uzbekistan by the centre as a supply base for the Union and its lop-sided economic development occasioned severe stagnation in all sectors. In the late 1980s Uzbekistan ranked twelfth in the USSR in terms of GDP, its per capita income being half the Union average. Serious problems were encountered in public health and housing. Hope of overcoming the systemic crisis appeared with Perestroika, an ill-fated attempt at restructuring the Soviet state which was proclaimed by Mikhail Gorbachev in April 1985. Fearful of separatist tendencies, the Union government engineered the notorious "Cotton Case", allegedly aimed at fighting corruption among high Uzbek officials. More than 25,000 managers and officials were arrested in Uzbekistan during this full-scale campaign, and persecution began of "nationalism", that is, any display of Uzbek traditions and culture. An unwritten government policy was launched to restrict the use of the Uzbek language. A new policy consistent with national interests began to form when Islam Karimov took the lead in the national government. Karimov was elected President of Uzbekistan at the 1st Session of the Supreme Council of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic in March 1990. Presidential decrees, acts, resolutions of the Supreme Council and the government, and finally, the Declaration of Independence were all designed to secure political and economic independence and the national revival of Uzbekistan. In 1989 Uzbek was made the official language of the new state, and a package of measures was drafted to address the most urgent economic problems, such as the monoculture of cotton, and to assist revival of Uzbek culture.

Overwhelming popular support for independence and the government line was expressed during presidential elections and a referendum on political sovereignty (29 December 1991). Islam Karimov won 86% of the vote and became the first President of the new Uzbek state; 98.2% of the population voted for independence. From September 1991 to July 1993 the Republic of Uzbekistan was officially recognised by 160 states. On 2 March 1992 the country joined the United Nations. Since independence, an era of free development began in the history of the Uzbek people. |

The history of Uzbekistan, rich in dramatic and epoch-making events, can be traced back to the dawn of mankind. There is archaeological evidence that the area of present-day Uzbekistan was populated by humans as early as the Palaeolithic Age (500,000-1,000,000 years ago).

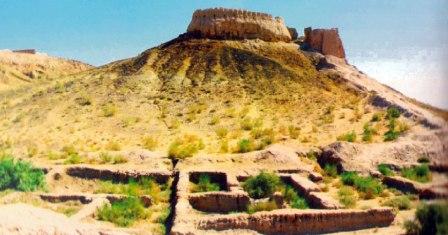

The history of Uzbekistan, rich in dramatic and epoch-making events, can be traced back to the dawn of mankind. There is archaeological evidence that the area of present-day Uzbekistan was populated by humans as early as the Palaeolithic Age (500,000-1,000,000 years ago). In the 7th-6th centuries BC the historic provinces of Bactria, Margiana, Khoresm and Sogdiana first emerged, as did the ancient cities of Maracanda, Kok-Tepa, Uzun-Kyr and Er-Kurgan, which had an area of hundreds of hectares and were surrounded by fortified walls.

In the 7th-6th centuries BC the historic provinces of Bactria, Margiana, Khoresm and Sogdiana first emerged, as did the ancient cities of Maracanda, Kok-Tepa, Uzun-Kyr and Er-Kurgan, which had an area of hundreds of hectares and were surrounded by fortified walls. The rule of the Achaemenids was ended by the advance of Alexander the Great who, having crushed the main body of Persian armies, invaded Central Asia in 329 BC in pursuit of Bess, satrap of Bactria and the last heir to the Achaemenid throne. Alexander spent three years (329-327 BC) subduing Central Asian peoples, faced by fierce resistance from the Sogdians led by Spitamen. Probably, the same period saw the rise of the first Uzbek political entity – the kingdom of Khoresm.

The rule of the Achaemenids was ended by the advance of Alexander the Great who, having crushed the main body of Persian armies, invaded Central Asia in 329 BC in pursuit of Bess, satrap of Bactria and the last heir to the Achaemenid throne. Alexander spent three years (329-327 BC) subduing Central Asian peoples, faced by fierce resistance from the Sogdians led by Spitamen. Probably, the same period saw the rise of the first Uzbek political entity – the kingdom of Khoresm. Throughout the period of local antiquity (1st century BC – early 3rd century AD) Northern Bactria was a province of the powerful Kushan Empire, which was founded in the 1st century AD by the Yue-chi chieftain Kadphises. Sogd (present-day Kashkadarya and Samarkand viloyats (regions) of Uzbekistan) at that time was an independent kingdom under the Girkoda dynasty, who are also believed to be of Yue-chi origin. In Khoresm, the Afrigid kings rose to power; judging from their dynastic symbol – a horseman – their rule continued for 700-800 years. Bukhara, Davan (Fergana) and, possibly, Chach enjoyed virtual independence, although these Transoxianian kingdoms might have been nominal dependencies of Kangyui.

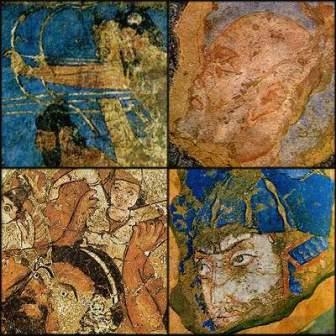

Throughout the period of local antiquity (1st century BC – early 3rd century AD) Northern Bactria was a province of the powerful Kushan Empire, which was founded in the 1st century AD by the Yue-chi chieftain Kadphises. Sogd (present-day Kashkadarya and Samarkand viloyats (regions) of Uzbekistan) at that time was an independent kingdom under the Girkoda dynasty, who are also believed to be of Yue-chi origin. In Khoresm, the Afrigid kings rose to power; judging from their dynastic symbol – a horseman – their rule continued for 700-800 years. Bukhara, Davan (Fergana) and, possibly, Chach enjoyed virtual independence, although these Transoxianian kingdoms might have been nominal dependencies of Kangyui. Radical changes to the antique social structure took place over the early Middle Ages (5th-8th centuries), when large landowners, dikhans, formed into an influential class. The political situation in this period was determined by the struggle for control of Transoxiana between the neighbouring powers: Sassanidian Iran and the Ephthalite kingdom (5th-6th centuries), Iran and the Turkic khanate (6th-7th centuries) and, finally, the Turkic khanate, Tang China and Arab caliphs which ended with the region’s inclusion in the Abbasid caliphate in the 8th century.

Radical changes to the antique social structure took place over the early Middle Ages (5th-8th centuries), when large landowners, dikhans, formed into an influential class. The political situation in this period was determined by the struggle for control of Transoxiana between the neighbouring powers: Sassanidian Iran and the Ephthalite kingdom (5th-6th centuries), Iran and the Turkic khanate (6th-7th centuries) and, finally, the Turkic khanate, Tang China and Arab caliphs which ended with the region’s inclusion in the Abbasid caliphate in the 8th century. The 9th-13th centuries. This dramatic epoch, which corresponds to the climax of medieval culture in the West, can be divided into two periods: the 9th-10th centuries, when the Takhirid and then Samanid rulers hold power under the religious and to some extent political leadership of Abbasid caliphs; and the 11th-13th centuries, when the Persian dynasties were replaced by a succession of Turkic rulers (the Karakhanids, Seljukids, Gaznevids and Anushteginids), and the influence of the caliphs was confined to spiritual leadership. Restoration of the native Central Asian state systems occurred in the 9th-10th centuries, when the unity of the Arab caliphate was broken both in the West (in Morocco, North Africa and Andalusia) and East (in Khorasan and Maverannahr).

The 9th-13th centuries. This dramatic epoch, which corresponds to the climax of medieval culture in the West, can be divided into two periods: the 9th-10th centuries, when the Takhirid and then Samanid rulers hold power under the religious and to some extent political leadership of Abbasid caliphs; and the 11th-13th centuries, when the Persian dynasties were replaced by a succession of Turkic rulers (the Karakhanids, Seljukids, Gaznevids and Anushteginids), and the influence of the caliphs was confined to spiritual leadership. Restoration of the native Central Asian state systems occurred in the 9th-10th centuries, when the unity of the Arab caliphate was broken both in the West (in Morocco, North Africa and Andalusia) and East (in Khorasan and Maverannahr). In 892 Ismail ibn Ahmad ascended the throne and embarked on an ambitious struggle to convert Maverannahr into a major power in the Muslim world. Under his rule, his state embraced the territory of present-day Uzbekistan, the northeast provinces of Iran, part of Afghanistan and South Kazakhstan; Bukhara was his capital.

In 892 Ismail ibn Ahmad ascended the throne and embarked on an ambitious struggle to convert Maverannahr into a major power in the Muslim world. Under his rule, his state embraced the territory of present-day Uzbekistan, the northeast provinces of Iran, part of Afghanistan and South Kazakhstan; Bukhara was his capital. The khanate in turn split into two parts: the eastern, with capital at Balasagun (in present-day Kyrgyzstan) and the western, with capital at Taraz, South Kazakhstan, and later at Kashgar. The ethnic composition of the khanate was dominated by the Turkic tribes of Karluks, Chigili and Yagma. In the late 10th century the Karakhanids began to attack Maverannahr, and in the beginning of the 10th century they defeated the Samanids and annexed their territory almost entirely. The only provinces which escaped subjugation were Khoresm, governed by Mamun from the house of the Iraqids, and Termez under the Gaznevid sultan Mahmud.

The khanate in turn split into two parts: the eastern, with capital at Balasagun (in present-day Kyrgyzstan) and the western, with capital at Taraz, South Kazakhstan, and later at Kashgar. The ethnic composition of the khanate was dominated by the Turkic tribes of Karluks, Chigili and Yagma. In the late 10th century the Karakhanids began to attack Maverannahr, and in the beginning of the 10th century they defeated the Samanids and annexed their territory almost entirely. The only provinces which escaped subjugation were Khoresm, governed by Mamun from the house of the Iraqids, and Termez under the Gaznevid sultan Mahmud. In the 12th century the Anushteginids, a dynasty of Turkic shahs from Khoresm, rose to power. Sultan Tekesh (1172-1200) took Khorasan and West Iran from the Seljukids. His son Muhammad (1200-1220) repulsed the Kara-Kitai and Gurid armies, and quelled a popular uprising in Khorasan and a revolt staged by Malik Sanjar in Bukhara. In 1210 Muhammad executed Usman, the last Karakhanid ruler of Samarkand, and in two years unseated the rulers of other former Karakhanid provinces. Having disposed of internal rivalry, Muhammad conquered Iran and Afghanistan. His military success eventually led to the rise of the powerful state of Khoresm shahs with capital at Gurganj (Kunya-Urgench).

In the 12th century the Anushteginids, a dynasty of Turkic shahs from Khoresm, rose to power. Sultan Tekesh (1172-1200) took Khorasan and West Iran from the Seljukids. His son Muhammad (1200-1220) repulsed the Kara-Kitai and Gurid armies, and quelled a popular uprising in Khorasan and a revolt staged by Malik Sanjar in Bukhara. In 1210 Muhammad executed Usman, the last Karakhanid ruler of Samarkand, and in two years unseated the rulers of other former Karakhanid provinces. Having disposed of internal rivalry, Muhammad conquered Iran and Afghanistan. His military success eventually led to the rise of the powerful state of Khoresm shahs with capital at Gurganj (Kunya-Urgench). The conquest of Iran and Iraq took Amir Temur more than a decade. His major advances were made during the campaigns of 1386-1389 and 1392-1397, although the first attacks on Khorasan were mounted by him in 1381. Next his armies overran Transcaucasia, and during the seven-year expedition (1399-1404) Amir Temur defeated the Ottoman Turks and took Egypt and Syria from the Mamelukes. In 1398 North India was subdued. The main foe of Amir Temur, khan Tokhtamysh of the Golden Horde, was utterly routed twice, in 1391 and 1395. By 1403 Amir Temur’s empire grew to an enormous size, embracing Central Asia and all of the Near and Middle East from the Mediterranean to North India. He distributed these vast possessions among his sons and grandsons (Timurids) as hereditary domains. Amir Temur died on 9 February 1405 in Otrar, en route to China. After his death his empire began to decline, remaining nearly as big only under Shahrukh (1409-1447). At that time Maverannahr was governed by the brilliant statesman Ulugbek (killed in 1449).

The conquest of Iran and Iraq took Amir Temur more than a decade. His major advances were made during the campaigns of 1386-1389 and 1392-1397, although the first attacks on Khorasan were mounted by him in 1381. Next his armies overran Transcaucasia, and during the seven-year expedition (1399-1404) Amir Temur defeated the Ottoman Turks and took Egypt and Syria from the Mamelukes. In 1398 North India was subdued. The main foe of Amir Temur, khan Tokhtamysh of the Golden Horde, was utterly routed twice, in 1391 and 1395. By 1403 Amir Temur’s empire grew to an enormous size, embracing Central Asia and all of the Near and Middle East from the Mediterranean to North India. He distributed these vast possessions among his sons and grandsons (Timurids) as hereditary domains. Amir Temur died on 9 February 1405 in Otrar, en route to China. After his death his empire began to decline, remaining nearly as big only under Shahrukh (1409-1447). At that time Maverannahr was governed by the brilliant statesman Ulugbek (killed in 1449).  The Timurid empire eventually found itself defenceless in the face of external threats. The most formidable enemy for the rulers of Khorasan and Maverannahr was khan Shaibani.

The Timurid empire eventually found itself defenceless in the face of external threats. The most formidable enemy for the rulers of Khorasan and Maverannahr was khan Shaibani. In 1747 Muhammad Rakhim, emir of the tribe of Mangits, rose to power in Bukhara, thus establishing the dynasty of the Mangits. The khanate of Bukhara became an emirate which existed until 1920. It attained its peak of power during the reign of the emirs Shahmurad (1785-1800) and Narsulla (1826-1866), who controlled most of Maverannahr, northern Afghanistan including Balkh and part of Turkmenistan.

In 1747 Muhammad Rakhim, emir of the tribe of Mangits, rose to power in Bukhara, thus establishing the dynasty of the Mangits. The khanate of Bukhara became an emirate which existed until 1920. It attained its peak of power during the reign of the emirs Shahmurad (1785-1800) and Narsulla (1826-1866), who controlled most of Maverannahr, northern Afghanistan including Balkh and part of Turkmenistan. In Khoresm, power was taken by Muhammad Amin (1763-1790), emir of the Kunrdads. His son Eltuzar assumed the title of khan in 1804, and the dynasty ruled the khanate of Khiva until 1920.

In Khoresm, power was taken by Muhammad Amin (1763-1790), emir of the Kunrdads. His son Eltuzar assumed the title of khan in 1804, and the dynasty ruled the khanate of Khiva until 1920. Having lost their independence, the Uzbeks were deprived of the right to choose political path for development, and to express their will. Unrecoverable damage was done to the millennium-old Central Asian civilisation and culture. The Tsarist government put the military command of Turkistan in charge of all administrative affairs. The pyramid of power in the region ascended to the governor-general who was head of the military and civil administrations. The principal economic goal of the colonial policy was to turn the region into a raw material base to supply the Russian industry.

Having lost their independence, the Uzbeks were deprived of the right to choose political path for development, and to express their will. Unrecoverable damage was done to the millennium-old Central Asian civilisation and culture. The Tsarist government put the military command of Turkistan in charge of all administrative affairs. The pyramid of power in the region ascended to the governor-general who was head of the military and civil administrations. The principal economic goal of the colonial policy was to turn the region into a raw material base to supply the Russian industry. In October 1917 the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia The National Progressivists did not accept Bolshevism and continued the struggle for independence. In November 1917 the 4th Regional Muslims’ Congress declared the establishment of Turkiston Mukhtoriyati, a national political entity which embodied the principles of a state development programme drafted by the National Democrats.

In October 1917 the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia The National Progressivists did not accept Bolshevism and continued the struggle for independence. In November 1917 the 4th Regional Muslims’ Congress declared the establishment of Turkiston Mukhtoriyati, a national political entity which embodied the principles of a state development programme drafted by the National Democrats.  The situation was as difficult in industry. In the course of "socialist industrialisation" proclaimed in 1925, palpable progress was made in the effort to convert Uzbekistan from a purely agrarian society into an agrarian-industrial one. Towards 1940, 1,445 industrial enterprises were launched in the country. However, much like the Tsarist government, the Soviets encouraged the development of industries that were able to provide the central regions of the USSR with raw materials. As a result, Uzbekistan essentially remained a supply base with little value-added capacity.

The situation was as difficult in industry. In the course of "socialist industrialisation" proclaimed in 1925, palpable progress was made in the effort to convert Uzbekistan from a purely agrarian society into an agrarian-industrial one. Towards 1940, 1,445 industrial enterprises were launched in the country. However, much like the Tsarist government, the Soviets encouraged the development of industries that were able to provide the central regions of the USSR with raw materials. As a result, Uzbekistan essentially remained a supply base with little value-added capacity. The Soviet-German war of 1941-1945 was a dramatic ordeal for the Uzbek people and the whole of the Soviet Union, which became the central land front in World War II. During these years, a total of 1,433,230 people from Uzbekistan went away to fight (over 40% of the country’s workforce).

The Soviet-German war of 1941-1945 was a dramatic ordeal for the Uzbek people and the whole of the Soviet Union, which became the central land front in World War II. During these years, a total of 1,433,230 people from Uzbekistan went away to fight (over 40% of the country’s workforce). On 31 August, the 6th Extraordinary Session of the Supreme Council declared the political independence of the country, which was officially named the Republic of Uzbekistan. 1 September was proclaimed Independence Day.

On 31 August, the 6th Extraordinary Session of the Supreme Council declared the political independence of the country, which was officially named the Republic of Uzbekistan. 1 September was proclaimed Independence Day.